U.S. Route 385 in Nebraska

| Gold Rush Byway | ||||

US 385 highlighted in red | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by NDOT | ||||

| Length | 180.36 mi[1] (290.26 km) | |||

| Existed | 1958–present | |||

| Tourist routes | ||||

| Major junctions | ||||

| South end | ||||

| North end | ||||

| Location | ||||

| Country | United States | |||

| State | Nebraska | |||

| Counties | Deuel, Cheyenne, Morrill, Box Butte, Dawes | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

U.S. Route 385 (US 385) is a part of the United States Numbered Highway System that travels from Big Bend National Park in Texas to US 85 in Deadwood, South Dakota. Within the state of Nebraska, the highway is known as the Gold Rush Byway, one of nine scenic byways across the state.[2] The highway follows along the old Sidney-Black Hills trail which played a crucial role during the Black Hills Gold Rush in the late 1870s. It served as the primary route to transport gold and mining gear between Sidney, Nebraska and the Black Hills to the north. Today, the highway enters Nebraska in the southeastern portion of the Nebraska Panhandle on the state line with Colorado northeast of Julesburg and continues in a northerly direction to the South Dakota state line north of Chadron.

US 385 was an original entry in the initial development of the US Highway System in 1926. It originally ran from Comfort, Texas to Raton, New Mexico and did not come near Nebraska. In 1935, most of the routing of US 385 was resigned as US 87.[3] The current incarnation of US 385 was commissioned in 1959 bringing the highway into Nebraska along the new alignment that stretched from Big Bend all the way to Deadwood, South Dakota in the Black Hills.[4]

Route description

Colorado to Bridgeport

US 385 enters Nebraska on the Colorado state line northwest of Julesburg, Colorado. Traveling to the northwest through agricultural fields and alongside Lodgepole Creek, the highway passes beneath I-80 just before it enters the small city of Chappell. The highway has a connection to I-80 south of town via Link 25A. Here, the highway meets up with US 30, the Lincoln Highway, running concurrently with it for about 25 miles to the northwest passing through Lodgepole before turning west and passing through the small communities of Sunol and Colton. At the highway approaches Sidney, US 385 breaks off from US 30 and turns north along the east side of Sidney.[5]

After departing Sidney, US 385 travels north as it begins its trek into the vast agricultural fields of the rural Nebraska Panhandle. A couple miles north of Sidney, the highway comes alongside the BNSF Railway which it runs parallel with for the next eighty miles with a few deviations. Continuing north through the small towns of Gurley and Dalton the landscape takes on a bit of change as the highway approaches somewhat rugged terrain as it descends 400 feet (120 m) into the North Platte River Valley. As US 385 approaches the North Platte River it joins up with N-92, the state's longest highway. Here, it takes a westerly turn towards Bridgeport, a town which takes its name from the Camp Clarke Bridge constructed in 1876 three miles to the west.

As the highway approaches Bridgeport from the south it joins up with US 26 to cross the North Platte River. On the south side of town, US 26 continues to the west where it passes Chimney Rock National Historic Site just twelve miles down the road. Continuing north across the river the two highways diverge, with US 26 heading east towards Broadwater and Ogallala while US 385 resumes its northward heading. For a brief few miles the roadway is, again, surrounded by agricultural fields, brought to life with center pivot irrigation north of Bridgeport. The highway transitions into slightly rugged terrain as it climbs back up, 400 feet, out of the valley.[5]

Bridgeport to South Dakota

The highway comes to a junction with Link 62A north of Bridgeport. Here, the Heartland Expressway joins US 385 from the west, a high priority corridor between Denver and Rapid City, South Dakota. Just a couple miles after this junction, the highway quickly passes through the unincorporated community of Angora. As the highway continues northeast from here, it enters the western reaches of the Nebraska Sandhills for about fifteen miles before it arrives in Alliance to meet up with N-2 just west of a large BNSF railyard. Alliance is home to Carhenge, a replica of England's Stonehenge constructed with vintage American automobiles. The concurrent highways leave Alliance to the northwest and after a few miles diverge. US 385 turns to the north, while N-2 continues to the northwest, taking the BNSF railway with it. As US 385 continues north it passes through additional spotty portions of the sandhills as it travels over forty miles without encountering any towns.[5]

South of Chadron the highway passes through Chadron State Park in the Pine Ridge Ranger District of the Nebraska National Forest. This area is part of an escarpment that lies between the Niobrara and White Rivers. Forested buttes, ridges and canyons have been carved into the high tableland. Sharing similarities with the Black Hills, the area is forested with Ponderosa Pine and contains a variation of wildlife such as bighorn sheep, elk, and mule deer, which are not common elsewhere in the state. The highway then enters Chadron where it joins US 20 along the west side of the city. It runs concurrently with US 20 to the west for two miles before departing to the north. US 385 then passes the Chadron Municipal Airport before turning to the northwest where it reaches the South Dakota state line. From there it continues north into the Black Hills towards Deadwood, South Dakota.[5]

History

Black Hills gold rush

US 385 travels south to north through the Nebraska Panhandle which has been part of the state since it was acquired in 1803 as part of the vast Louisiana Purchase. Much of inland Nebraska, including the Panhandle became important regions for overland travel via horse and wagon. This included the California, Mormon, and Oregon trails as well as the Pony Express route which passed through the region. Settlers to Nebraska were mostly farmers, but the discovery of gold in Wyoming in 1859 sent a rush of speculators westward across the state.

In 1874, during the Black Hills Expedition led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, the discovery of gold in the region sparked the Black Hills Gold Rush. As prospectors located valuable sources of gold along Deadwood and Whitewood Creeks, thousands more prospectors entered the area looking to stake their claim. In April, 1876, a gold outcropping was discovered near Lead, South Dakota. This gold claim became the Homestake Mine and was the primary source of the placer gold being mined from the surrounding area. Over the next century, ten percent of the world's gold supply would come from this site.

Sidney, Nebraska became an important city during the gold rush. It was an optimal starting point for gold prospectors. It was adjacent to the Union Pacific Railroad and on established trails from the east, as well as to the north via the Sidney-Black Hills Trail. The trail was also preferred as it was shorter and through less treacherous terrain than trails to the west. The construction of Camp Clarke Bridge over the North Platte River in 1876, three miles west of modern-day Bridgeport also boosted its appeal. This allowed prospectors and freight to arrive via rail and continue north into the Black Hills with relative ease.[6] The bridge contained sixty-one wooden trusses and spanned nearly 2,000 feet (610 m). Tolls ranged between $2 and $6 per wagon and up to $10 for heavy freight wagons.[7][8]

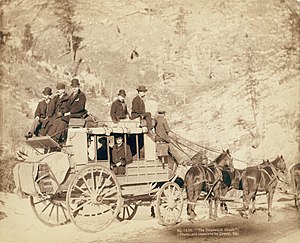

While prospectors flooded the area, along with them came those who would service the nascent mining industry. This included stagecoach lines that traveled between Sidney and the Black Hills carrying freight and passengers. Sometimes stagecoaches would depart Sidney for Deadwood three times each day. Conditions on the stagecoaches were usually cramped as upwards of sixteen people could be carried at a time. Between 1874 and 1880 most of the supplies and freight coming to and from the gold camps traveled this trail. Thousands of stagecoaches and wagons are estimated to have traveled the route during this time. At the peak of the gold rush in 1878 and 1879, fifty to seventy-five freight wagons left Sidney every day and an estimated 22-million pounds of freight traveled along the trail.[9]

Each week, gold was shipped out of the Black Hills to Sidney, sometimes with daily loads approaching $200,000 in value[10] (equivalent to $5.55 million in 2023[11]). It was during this time that stagecoach robberies became frequent occurrences. This became such a problem that the Gilmer and Salisbury stage lines manager, Luke Voorhees, attempted to capture the bandits to prevent loss of business along the route. When that wasn't enough, in 1878, he enlisted the help of Concord stagecoach builders, Abbot-Downing Company, to manufacture an armored stagecoach to withstand attacks. These armored stagecoaches were lined with half inch steel, portholes for windows and outfitted with an 800-pound steel safe accompanied by six to eight armed guards. Throughout three years of service, the armored stagecoach, nicknamed "Old Ironsides" was only robbed once.[12][13]

In 1880, a railroad between Chicago and Pierre, South Dakota severely damaged the freight business in Sidney. As the faster northerly route became preferred, freight companies moved their business to Pierre, mostly returning Sidney to the quieter times before the Gold Rush.

Predecessor highways

Most of the US 385 corridor was defined by the trails created during the Gold Rush, especially north of Sidney. Prior to the designation of US 385 in 1958 the route was covered by a combination of existing state highways. N-27 ran from the Colorado state line to Chappell where it met up with US 30. From there, US 30 carried the route west to Sidney then departed the city to the north along N-19. N-19 then continued along the rest of the modern day route north to the South Dakota state line passing through Bridgeport, Alliance, and Chadron.[14][15][16]

Future

Heartland Expressway

US 385 north of Link 62A east of Scottsbluff is part of the federally designated high priority corridor titled the Heartland Expressway that connects Rapid City, South Dakota with Denver, Colorado via improved four-lane divided highways.[17] The Heartland Expressway is a portion of a high priority international corridor between Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico and Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada called the Ports to Plains Corridor. This international corridor is made up of three high priority systems, of which the Heartland Expressway is one. The other two systems include the Theodore Roosevelt Expressway between Rapid City and Saskatoon and The Ports to Plains Corridor between Monterrey and Denver. Together, the systems complete an international trade corridor between the United States, Mexico, and Canada. Portions of the Heartland Expressway in Colorado and South Dakota are already complete, however progress has been slow in Nebraska. Prior to 2016, no portion of US 385 had been upgraded to four lanes in Nebraska, however portions of the expressway along US 26 between Morrill and Minatare as well as N-71 south of Scottsbluff to I-80 are upgraded to four-lane divided highway.[18]

Nebraska Link 62A to Alliance

In 2015, the environmental assessment for the section of US 385 between Link 62A and Alliance was approved by the Federal Highway Administration.[19] This 24.75 miles (39.83 km) segment would be constructed in three portions, the first of which got underway in 2016 and involved the stretch of US 385 between Alliance to 9 miles (14 km) south of town at an estimated cost of $23,655,000.[20] The second segment would cover the section of US 385 between Link 62A and the first segment south of Alliance. This 14.2 miles (22.9 km) portion of the project is slated for construction in 2018 at a cost of $31,182,000.[21] The third portion of this segment would involve construction of a sweeping curve between Link 62A and the newly upgraded US 385.

Alliance to Chadron

Original plans for the Heartland Expressway called for divided four-lane highways throughout, however the high cost of construction through 59 miles (95 km) of mostly rural area made the project cost prohibitive to be built at that standard. In September, 2016 Nebraska Governor Pete Ricketts announced $300 million in transportation projects to be funded via the Build Nebraska Act and the Transportation Innovation Act. Of the projects included, the US 385 corridor between Alliance and Chadron was slated for design work.[22] Rather than planning to construct this corridor as a four-lane divided highway, it will instead be planned as a Super 2 design at a projected cost of $89 million.[23]

Major intersections

| County | Location | mi[1] | km | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deuel | Swan Precinct | 0.00 | 0.00 | Continuation into Colorado | |

| 7.87 | 12.67 | ||||

| Chappell | 8.26 | 13.29 | Southern terminus of US 30 concurrency | ||

| Cheyenne | Lodgepole | 17.32 | 27.87 | ||

| Sunol | 24.50 | 39.43 | |||

| Sidney | 34.00 | 54.72 | Northern terminus of US 30 concurrency | ||

| Morrill | East Camp Clark Precinct | 65.78 | 105.86 | Southern terminus of N-92 concurrency | |

| Bridgeport | 73.44 | 118.19 | |||

| 73.91 | 118.95 | Southern terminus of US 26 concurrency; northern terminus of N-92 concurrency | |||

| 74.91 | 120.56 | Northern terminus of US 26 concurrency | |||

| Haynes Precinct | 84.84 | 136.54 | |||

| Box Butte | Alliance | 108.99 | 175.40 | Southern terminus of N-2 concurrency | |

| Box Butte-Wright Lake Precinct | 116.92 | 188.16 | Northern terminus of N-2 concurrency | ||

| Dorsey Precinct | 125.80 | 202.46 | |||

| Dawes | Precinct 7 | 134.90 | 217.10 | Box Butte State Recreation Area Road (Dunlap Road) | To Box Butte Reservoir State Recreation Area |

| Chadron | 161.62 | 260.10 | Southern terminus of US 20 concurrency | ||

| Precinct 2 | 163.80 | 263.61 | Northern terminus of US 20 concurrency; southbound access via unsigned L-23D | ||

| Precinct 6 | 180.36 | 290.26 | Continuation into South Dakota | ||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||

References

- ^ a b "Nebraska Highway Reference Log Book" (PDF). Nebraska Department of Roads. pp. 306–308. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ "Scenic Byways". Nebraska Department of Roads. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ Sanderson, Dale. "End of US highway 385[I]". US Ends.com. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ Sanderson, Dale. "End of US highway 385". US Ends.com. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Google (January 15, 2017). "Overview Map of US 385 in Michigan" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Mahnken, Norbert (1949). "The Sidney-Black Hills Trail". Nebraska History. 30 (3): 211.

- ^ "Camp Clarke Bridge and Sidney-Black Hills Trail". Nebraska State Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 2, 2004. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ McKee, Jim (December 7, 2014). "Henry T. Clarke an almost-forgotten Nebraska entrepreneur". Lincoln Journal Star. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ Mahnken (1949), p. 214

- ^ "Gold Rush Byway". America's Scenic Byways. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Mahnken (1949), pp. 222–224

- ^ "Abbott and Downing Company". American Western History Museums. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Nebraska Department of Roads & Irrigation (August 1, 1937). Nebraska State Highway System (PDF) (Map).

- ^ Nebraska Department of Roads & Irrigation (April 1, 1940). Nebraska State Highway System (PDF) (Map).

- ^ Nebraska Department of Roads (1955). State Highway System (PDF) (Map).

- ^ "Moving the Great Plains Forward". Heartland Expressway. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ Heartland Expressway Association (2017). Heartland Expressway Corridor Completion Status (Map). Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Heartland Expressway: Final Environmental Assessment" (PDF). Nebraska Department of Roads. November 5, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "District Five Fiscal Year 2016" (PDF). Nebraska Library Commission. Nebraska Department of Roads. p. 31. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Nebraska's Statewide Transportation Improvement Program FY 2017 thru FY 2020" (PDF). Nebraska Department of Roads. p. 90. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Gov. Ricketts, Roads Department Announce Major Roads Construction Projects" (PDF) (Press release). Lincoln, NE: Governor Pete Ricketts. September 22, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "US 385 from Alliance to Chadron" (PDF). Nebraska Department of Roads. Retrieved January 15, 2017.