Portage Glacier Highway

Portage Glacier Highway | |

|---|---|

| Whittier Access Road | |

Portage Glacier Highway highlighted in red | |

| Route information | |

| Maintained by Alaska DOT&PF | |

| Length | 11.59 mi[2][3] (18.65 km) |

| Existed | June 7, 2000[1]–present |

| Major junctions | |

| West end | |

| East end | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alaska |

| Boroughs | Municipality of Anchorage, Unorganized |

| Highway system | |

The Portage Glacier Highway, or Portage Glacier Road, is a highway located in the U.S. state of Alaska. The highway is made up of a series of roads, bridges, and tunnels that connect the Portage Glacier area of the Chugach National Forest and the city of Whittier to the Seward Highway. Most of the highway travels through mainly rural areas just north of the Kenai Peninsula, with the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel passing under Maynard Mountain, part of the Chugach Mountain Range. Parts of the route were first constructed in the early 1900s, and the entire highway was completed on June 7, 2000, as part of the Whittier Access Project. The main portion of the highway traveling from the western terminus to the Begich, Boggs Visitor Center at Portage Lake is designated as National Forest Highway 35 by the United States Forest Service (USFS).

Route description

The portion of the Portage Glacier Highway traveling from the Seward Highway to the Begich, Boggs Visitor Center is designated as part of Forest Highway 35, a Federal Forest Highway (FFH). Forest Highways are funded and administered by the USFS and the Federal Highway Administration;[4] the system was created by the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921.[5] FFH-35 is one of the 33 Forest Highways that are currently designated in Alaska.[6]

Chugach National Forest

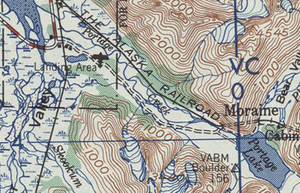

The Portage Glacier Highway begins at an at-grade intersection with the Seward Highway, in the former town of Portage.[7] At this point, the highway is a two-lane, asphalt road. Almost immediately after the Seward Highway intersection, the road crosses over the Coastal Classic line of the Alaska Railroad.[2] The highway continues in a southeasterly direction along the Portage Valley, with Portage Creek to the north and pine forests to the south. After about 1.2 miles (1.9 km), the roadway intersects a small gravel road that leads to the Moose Flats Day Use area, which has access to several scenic hiking trails.[2][8] Peaks of the Chugach Mountains, along with several hanging glaciers can be seen from the road; Portage Glacier is out of view. The highway passes through a low-lying wetland before reentering forest and providing access to the Alder Pond Day Use area and the Portage Valley RV park.[2][9]

Portage Glacier Highway continues southeastward, providing access to the Black Bear Campgrounds, maintained by the USFS. The roadway bends eastward, passing the USFS Williwaw Campgrounds, as well as several small gravel roads.[8] The road continues for a short distance before passing the Begich, Boggs Visitor Center and associated buildings, comprising the headquarters of Portage Glacier unit of the Chugach National Forest.[10] The highway continues onto the Portage Creek Bridge, which is 114 feet (35 m) long.[11] It allows the highway to cross over the small Portage Creek, which drains Portage Lake, in turn fed by Portage Glacier. The bridge ends at the start of the Portage Lake Tunnel. The tunnel is 445 feet (136 m) long[11] and constructed of concrete. The route proceeds on to a 0.5 mi (0.8 km) portion of road known as the "Rock Cut at Portage Lake" by the Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities (DOT&PF). This road passes along the coast of Portage Lake,[12] and borders a large, man-made cliff to the north (hence the name "Rock Cut"). This portion of the route terminates at the Placer Creek Bridge. The bridge, which is just 83 feet (25 m) long,[11] spans over Placer Creek, the smaller of the two creeks feeding Portage Lake. The highway continues to the six-lane Bear Valley Staging area, and the toll booth for the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel.[2] The road continues into the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel.[7]

Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel

The Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel, often called the Whittier Tunnel after the town at its eastern terminus, is a dual-use ("bimodal") highway and railroad tunnel that passes under Maynard Mountain. At a length of 13,300 ft (4,100 m), or 2.51 miles, it is the longest highway tunnel and longest combined rail and highway tunnel in North America. The tunnel originated as a rail-only tunnel excavated in 1941–42. The tunnel was upgraded to bimodal use by the Kiewit Construction Company between September 1998 and mid-summer 2000.[13][14]

The redesigned tunnel is fitted with a combined single uni-directional highway lane and single-track railway. The floor of the tunnel is constructed of 1,800 texturized concrete panels, each 7.5 by 8 feet (2.29 by 2.44 m), with the railroad tracks sunken slightly below the road surface.[15] The interior is exposed rock, and contains several "safe-houses", which are small buildings that are used in case of severe earthquakes, vehicle fires, or other emergencies. The tunnel also contains several pull-outs, which are reserved for disabled vehicles.[7] As motor vehicle speed in the tunnel is limited to 25 miles per hour (40 km/h), it takes about ten minutes to travel from end to end. The tunnel uses a combination of portal fans and reversible jet fans to ensure proper air flow and air quality throughout the tunnel.[14] There are two backup generators to ensure that the computerized traffic controls and safe-house ventilation systems in the tunnel continue to function in the event of a power failure.[13]

The tunnel can accommodate either eastbound traffic, westbound traffic, or the Alaska Railroad but only one at any given time. Because rail and road traffic must share the tunnel, it is coordinated by two computer-based systems — the Tunnel Control System and the Train Signal System. These systems control the timing of vehicles entering the tunnel, spacing them for safety, and lower railroad gates when a train is approaching.[13] The tunnel's entrance portals are designed in an A-shape, with a large, train-sized "garage door", which allows traffic in and out of the tunnel. The entrance portals are designed to withstand the force of an avalanche.[15] The tunnel's eastern terminus is in Whittier.[2][7] The staging areas on either end of the tunnel can accommodate as many as 450 vehicles waiting to pass through.[13]

Vehicle convoys enter the tunnel in alternating directions every half hour.[16] Scheduled and unscheduled trains can cause delays of up to 30 minutes. The tunnel operates from early morning until late evening on a schedule that varies seasonally and according to construction and maintenance needs.[17] Larger or heavier vehicles have to be carried as rail transport.[18] Pedestrians and bicycles are prohibited.[19]

Track circuits in the tunnel had problems because of moisture; in 2015 these were replaced with axle counters.[20]

Whittier

After exiting the tunnel, the highway enters the nine-lane Whittier staging area, where it passes several of the tunnel's automated control systems. Before traveling past the single-runway Whittier Airport, the route intersects two small roads, one of which is the Portage Pass Trail access route.[21] Running parallel to the Alaska Railroad line, the route - now named West Camp Road - continues between the Passage Canal and several mountains for approximately 0.5 miles (0.80 km). Passing by the Cliffside Marina and the Alaska Railroad Whittier Depot, the route crosses over Whittier Creek before immediately making a left onto Whittier Street, crossing the railroad and bending southeastward and traveling past a large parking lot, the headquarters. Traveling past several businesses making up central Whittier as well as the city park, used for Whittier Parking and Camping, the highway turns east and intersects Glacier Avenue, as well as a short pedestrian pathway. The roadway continues through central Whittier before reaching a four-way intersection with Blackstone Road, Eastern Avenue, and Depot Road, after which the route transfers to the latter. The road continues along Passage Canal for a short distance, while traveling towards the Alaska Marine Highway (AMHS) pier. Depot Road splits away from the highway, which continues for a short distance along Dock Access Road before reaching its eastern terminus, the AMHS pier.[8][21]

Traffic

The highway is maintained by the Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities (AkDOT&PF). Part of the job of the AkDOT&PF is to measure traffic along the highway. These counts are taken using a metric called annual average daily traffic (AADT). This is a statistical calculation of the average daily number of vehicles that travel along a portion of the highway. The estimated AADT for the Portage Glacier Highway is 1,030 vehicles.[22] In addition to taking AADT, the AkDOT&PF also takes monthly and yearly counts for the highway. The road's yearly traffic count for 2010 was 234,738 vehicles.[23] The roadway's highest monthly traffic is in mid-summer, when an average of nearly 50,000 vehicles use the tunnel each month. The highway's lowest monthly traffic is in late winter, when the average monthly traffic is only about 6,000. The monthly and yearly counts are taken at the entrance to the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel.[23] The entire length of the highway is designated as an Intermodal Connector Route,[24] part of the National Highway System (NHS),[25] a network of roads important to the country's economy, defense, and mobility.[26]

Scenic and recreational opportunities

The Portage Glacier Highway offers numerous scenic and recreational opportunities, mostly located along the section designated as FFH-35. A short, 0.25 miles (0.40 km) long boardwalk trail and the 4.6 miles (7.4 km) long Trail of Blue Ice are accessible through the Moose Flats Day-Use area.[2][27] A viewing area for the Explorer Glacier is located near milepost 2, and a turnout for the Portage River is located near milepost 3. Near milepost 4 is the Williwaw fish viewing observation deck, which allows travelers to view spawning salmon in July through September. The 2 miles (3.2 km) long loop Williwaw Nature Trail is accessible through the Williwaw Campground. The trail provides views of the Middle Glacier.[2][8] At the turnout for the Begich, Boggs Visitor Center is the Byron Glacier Trail as well as several others. The Portage Glacier can be seen on a short cruise on the M/V Ptarmigan; the glacier is no longer visible from the road.[2] Past milepost 6 is a turnout for the Byron Glacier and Portage Lake.[2][8]

Moose can be seen along the highway, as well as black and brown bears. Bald eagles can occasionally be seen from the highway.[2][8] During spring and autumn, migrating species of ducks, geese, swans, and cranes can be seen throughout the region.[28] Spawning salmon species of sockeye, chum, and coho can be seen in Portage Creek.[8] Several unique species of wildflowers are found along several of the trails in the area.[27] Whittier annually holds the Walk to Whittier, which is an event where pedestrians walk through the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel to Whittier, the only time pedestrians may use the tunnel. The event has been held since 2002, except it was not held in 2010. The walk traditionally takes place in June.[29]

Tolls

A toll is charged for access through the Anton Anderson Tunnel. The fees are collected from vehicles traveling eastbound. The fee for a regular vehicle is $13, as is the price for motorcycles. Vehicles pulling trailers must pay a higher toll, set at $22. Small buses and regular RVs are charged $38, while large buses must pay $137. Oversize and unusually sized vehicles, those 10 to 11 feet (3.0 to 3.4 m) wide and 14 to 15 feet (4.3 to 4.6 m) high must pay $330 per use. Vehicles that are exempt from paying tolls are those owned by the Alaska Railroad, the DOT&PF, or any emergency or law enforcement vehicle. Any vehicles owned or operated by any state government agency or school district pay $11.[30]

Seasonal passes are also available for normal-sized cars, trucks and motorcycles, and are priced at over $600.[30] The average passenger vehicle toll cost per mile is $39.42, while the average per-mile vehicle price for trucks is $39.52.[31] The tunnel is operated on a strict time schedule, with vehicles being allowed in for 15 minutes from each direction before alternating to the other. The tunnel is open from 5:30 a.m. to 11:15 p.m. during summer months, and from 7:00 a.m. to 10:45 p.m. during winter months.[32]

History

Native trail

The earliest evidence of the Portage Valley being used for transportation dates back to early A.D, when the Inuit used the flat, low-lying valley as a pass through the Chugach Mountains.[33][34] The Dena'ina people continued using the valley as a passage between Cochrane Bay and the Turnagain Arm. They used Portage Creek for fishing purposes and established a series of trails along the creek.[33][35] Russian fur traders and early settlers continued to use the valley, establishing a trail along the creek and the Portage and Burns glaciers.[33][36] It was possible for boats to travel through the valley by using the Passage Canal and the creek up until 1913. The trail was usable until 1939, due to the continuous recession of the Portage Glacier. The final party to attempt to use the trail that year was forced to climb 3,000 feet (914 m) up the Portage Shoulder to avoid the drop-offs and crevasses that had formed along the trail.[37]

Railroad development

... (A hub) of roads will grow out of Anchorage because of its strategic location as the head of defenses in the Territory. The switching of the railroad from Seward to Portage Bay will also come within the near future, and for the same reason.

General Simon Buckner, the U.S. Armed Forces plan for Alaska, October 15, 1940.[38]

In 1940, the U.S. Government realized that it needed to reevaluate its territories, including Alaska. Alaska was declared a vulnerable attack target, as was the existing railroad connecting Anchorage and Seward. The U.S. Armed Forces began planning for new roads and railroads, and on October 15, 1940, General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr. announced those plans. The plan called for the existing railroad to be transferred to Whittier, and for the construction of a road to Seward (the Seward Highway), a road to the Richardson Highway (the Glenn Highway and the Tok Cut-Off), and a road to the Portage Valley (the Portage Glacier Highway). Less than a week after the announcement of the plan, surveying of the area around Whittier was taking place in order to make sure of the safety of building the railroad terminal. The project was strongly opposed by the city of Seward, but after the survey was complete, the project was definite.[38]

In early 1941, large groups of people from the Kenai Peninsula traveled to Washington, D.C. to protest the moving of the railroad. Despite the opposition, on April 3, 1941, U.S. Congress passed a bill providing the project with $5.3 million (equivalent to $109,789,100 respectively in 2023[39]). In late April, the U.S. Army's 177th Engineering group began work on clearing and grading the former native trail.[38] The U.S. Army hired the West Construction Company of Boston, Massachusetts, to assist in the construction of the future railroad's two tunnels. West Construction and the Army began working on the tunnel under Mount Maynard in late August 1941. The first boring of the tunnel began on the east side of the mountain, and shortly afterwards, construction on the west side began. Winter hindered the construction of the tunnel until mid November, when a small "snowshed" building was constructed. The U.S. entered World War II on December 8, 1941, after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. This sparked the need for the completion of the tunnel earlier than expected. By the end of 1941, workers had tunneled more than 170 feet (52 m) into Maynard Mountain.[38]

Work on the tunnel rapidly increased into the summer of 1942. Large areas of the rock were blasted away with dynamite. The material removed from the tunnel was used as grading material for other parts of the railway. Supplies were received behind schedule, mainly due to the war. This hindered progress on the tunnel. In June 1942, Japanese forces attacked and invaded the Alaskan islands of Attu and Kiska, again provoking the need to complete the tunnels sooner. The winter conditions of 1942 and 1943 slowed the progress of the tunnels.[38] Work on the railroad continued until April 23, 1943, when the project was completed.[40] Anton Anderson, the lead engineer for the tunnels and namesake for the tunnel to Whittier, was not present when the railroad was used for the first time, fearing the Whittier Tunnel was not ready.[41]

Early roads

The U.S. army established a series of simple earthen roads while constructing the railroad spur. This was the first road to exist in the Portage Valley.[42] Whittier began to grow after the completion of the railroad spur. The port boomed in the mid-1940s, with the population reaching over 1,000. The city, including roads, began to form.[40] By 1953, the earthen road in Portage Valley had generally been relocated near the location of the present highway.[43] Also around that time, a road in Whittier in the location of the present highway existed as a graded, dirt road.[44] The highway was probably paved sometime between 1965 and 1967, and three small bridges along the route were constructed, all of which are still used today.[45][46]

Highway studies and proposals

Between the late 1950s and the early 1960s, the U.S. military pulled out of Whittier, allowing the town to grow as a commercial port. Whittier's location made it a large tourist location, and after the military pullout, travel to Whittier grew massively. In addition to the state's paving of the highway, the Alaska Railroad began offering shuttle services between Portage and Whittier in the mid-1960s. The Alaska Railroad would allow vehicles to drive onto flatcars, which would then be transported by train through the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel to Whittier.[40] The number of people visiting Whittier grew progressively, bringing with it a larger number of requests for a more convenient and affordable way of transportation to Whittier.[47] During the late 1970s, a proposal was put forward for a road to Whittier. In preparation for the highway, Anchorage businessman Pete Zamarello purchased the Buckner Building, and planned to convert it into a resort. However, the highway proposal fell through.[48] In 1981, the AkDOT&PF began to study possible alternatives to the railroad, which would have cost anywhere between $10 million and $68 million.[49]

In 1993, the AkDOT&PF finally initiated the study for the alternative transportation system to Whittier. The project would be named the "Whittier Access Project".[40] The AkDOT&PF authorized HDR Alaska to conduct the study. The study presented five solutions — increasing the existing flatcar service, installing a high-speed electric rail service, constructing a series of highways over the mountain range, building a highway and tunnels through the mountain range, and constructing a highway to the existing railroad tunnel and expanding the tunnel to withstand motor vehicles.[47] After consulting with members of the Alaska Railroad, the general public, and highway and tunnel engineers, the AkDOT&PF decided to proceed with the last option, involving the expansion of the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel and the construction of a highway. In November 1995, an environmental impact statement, created by HDR Alaska, was approved by the Federal Highway Administration, allowing the project to proceed.[40]

Whittier Access Project

In March 1996, the state of Alaska announced its final plans for the construction of the Whittier Access Project. The project was predicted to cost around $50 million, and the project was planned to begin later that year.[50] However, the project was met with much controversy, and by December 1996, the project still had not begun. The cost of construction was reevaluated to be around $60 million, and the project was planned to begin in March 1997.[51] Construction of the Whittier Access Project finally began on May 6, 1997. Then-governor of Alaska Tony Knowles began the construction when he detonated six pounds of explosives located on Begich Peak, although this was unrelated to the project.[52] On May 22, 1997, construction of the project was halted.[53] Carl S. Armbrister, the Director of the Office of Planning and Program Development for the Federal Highway Administration's 10th Region and head of the project was sued by several environmental agencies and tourism groups, headed by the Alaska Center for the Environment (ACE).[54][55] The ACE brought the suit against Armbrister on the grounds that the project violated section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act of 1966, which requires that all environmental impacts of a project be assessed and that a project "[has] no feasible and prudent alternative".[55][56] The ACE held that a new highway was not needed and improving the existing rail service was a prudent and feasible option.[55] However, one day after construction was stopped, a judicial ruling was issued permitting work to continue.[57] Construction continued for a week, until May 31, but was then halted again due to the lawsuit. Work on the project was ruled off until at least mid-July of that year.[58]

[u]nlike the city of Memphis, Alaska is not limited to a few `green havens.' ... In a very real sense the entire State of Alaska, 1/5 the size of the continental United States, is a giant park.

District judge James Keith Singleton, Jr.'s opinion[54]

James Keith Singleton, Jr., the district judge overseeing the case, ruled in favor of Armbrister and the Federal Highway Administration and stated that the agency was correct in its decision against improved rail service. The suit was compared to the landmark 1971 case Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, wherein the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in favor of Memphis, Tennessee citizens attempting to protect Overton Park from a plan to route Interstate 40 through 26 acres (11 ha) of its forest. However, unlike in that case, the Whittier Access project was found to be the only feasible solution for a link to Whittier. The ACE appealed the decision and the case went to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The court upheld Singleton's decision, finding that the project only affected a very small amount of parkland and that the road was necessary to meet the requirements for a link to the city. These rulings were legally significant as they appeared to overturn the precedent established in the Overton Park case, which was interpreted as saying that "it must be shown that the implications of not building [a] highway pose an 'unusual situation'".[54]

Work on the project was finally approved following the Ninth Circuit's decision. The lawsuit had put the project, which had been planned to be completed by the end of 1998, far behind schedule. The first phase of construction consisted of building the Portage Creek Bridge and the construction of a new tunnel through Begich Peak. The contract for the phase had been awarded prior to the lawsuit, but work on the components was not completed until very late in 1998. A temporary bridge was built over Portage Creek so that the tunnel could be constructed.[42][59] The final part of the phase was replacing the temporary bridge over Portage Creek. The structure was designed so that it would appear to fit with the environment but could also withstand the regular seismic activity of the region and have a minimal impact on the surrounding fish and plant populations.[60][61] CH2M Hill was selected to design the approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 km) of highway that would connect the existing road to the Anton Anderson Tunnel. Construction of the highway, done by Herndon and Thompson Inc., was finished before tunnel work began.[40][42]

The Kiewit Construction Company, based in Omaha, Nebraska, was awarded the contract for phase two, redesigning the Anton Anderson Tunnel. Kiewit began planning the tunnel design in June 1998, and began work on the project sometime around September.[42] The first part of the tunnel construction involved vertically and horizontally expanding the existing rock walls. Beginning from the western entrance, Kiewit drilled away several feet of the rock face from the top of the tunnel and installed a net to prevent any potential rockfalls. They then drilled sideways, clearing space for the nine vehicle turnaround areas.[42] However, work on the tunnel was hindered by several different events. While crews were working on the tunnel, a drunken Whittier resident drove his or her truck into the tunnel and got it stuck on the rails.[62] On October 23, a thirteen-car train derailed at the western entrance. Although no workers were injured, a substantial amount of the equipment was destroyed.[42] In addition to the accidents, crews had to work in extreme weather. Kiewit claims that workers had to deal with "winds of more than 120 mph, minus 40 degree temperatures and snow up to 43 feet deep" and wind chills that would drop to around −80 °F (−62 °C).[42][61] An avalanche also at one point halted construction for four days.[61]

Despite the conditions, the crews were forced to do much of the work during the winter, since the project had to adjust to the train schedule. Trains ran daily during the summer, so work was restricted to about nine-hour shifts during the night. During winter months, trains were only operating during four days each week. When a train was scheduled to come through the tunnel, crews reported they had to spend "up to two hours breaking down equipment, getting it all outside and waiting for the train to pass before heading back into the mountain".[61][63] Following expansion of the tunnel, one of the first steps the crews took was to demolish the existing entrance portals. Once they were destroyed, the existing rail was removed in sections. Pre-cast panels were laid where the tracks had been, before the old rail was put back and secured to the panels. While that was being completed, some crews installed a series of anti-icing insulation panels and drainage pipes to keep the tunnel clear during winter months.[42][63]

Construction work was completed on schedule, in early 2000.[42] The town of Whittier began a number of improvements to help adjust for the road's opening. Among these were more parking facilities and increasing public restrooms. The town government also approved of several long-term changes to the city that would begin after the road was opened, including a second harbor, a bicycle trail, a new sidewalk system, and shopping center.[64] The official opening ceremony was held on June 7 and was marked by protests from environmentalists. A group of three of them chained themselves together in the middle of the road in an attempt to block traffic, while another group of about twenty hung banners and waved signs. The ceremony was attended by around 300 people. Then-governor Knowles performed a ribbon-cutting and rode through the tunnel in a 1954-model Cadillac.[1]

Major junctions

| Borough | Location | mi[9][65] | km | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality of Anchorage | 0.00 | 0.00 | Western terminus. Western end of FFH-35 designation | ||

| 5.01 | 8.06 | Visitor Center access road. Eastern end of FFH-35 designation | |||

| 6.47 | 10.41 | Toll plaza | |||

| 6.82– 9.31 | 10.98– 14.98 | Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel | |||

| Unorganized | Whittier | 10.89 | 17.53 | Whittier Street | Portage Glacier Highway transfers to Whittier Street |

| 11.06 | 17.80 | Glacier Avenue | Access to central Whittier | ||

| 11.26 | 18.12 | Depot Road | Portage Glacier Highway transfers to Depot Road | ||

| 11.59 | 18.65 | Eastern terminus and access to Alaska Marine Highway ferry terminal | |||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||

Related route

| Location | Chugach National Forest |

|---|---|

| Length | 6.59 mi[6] (10.61 km) |

Forest Highway 35 (FFH-35) is a Federal Forest Highway located entirely within Chugach National Forest. The highway is approximately 6.6 miles (10.6 km) long, and is mostly designated along the Portage Glacier Highway. The road serves the Portage Glacier branch of the park. FFH-35 begins at an intersection with the Seward Highway (AK-1) in Portage. The route follows the Portage Glacier Highway for approximately 5 miles (8.0 km), passing several park campgrounds and scenic turnouts. FFH 35 turns off the Portage Glacier Highway onto Portage Lake Loop Road, passing west of the Begich, Boggs Visitor Center Complex. The designation then shifts from Portage Lake Loop Road to Byron Glacier Road, which proceeds southward past low-lying marshland along Portage Lake. It continues past a small turnout area and travels over a small creek before proceeding eastward to its eastern terminus, a building and parking lot that make up part of the visitor center.[9][66]

Major intersections

The entire highway is located within the Municipality of Anchorage, Alaska.

| mi[6] | km | Destinations | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.00 | Western terminus | |||

| 5.01 | 8.06 | Portage Glacier Highway | End of designation along Portage Glacier Highway | ||

| 5.12 | 8.24 | Portage Visitor Center Road | |||

| 5.37 | 8.64 | Byron Glacier Road | Beginning of designation along Byron Glacier Road | ||

| 6.40 | 10.30 | End of state alignment | State maintenance ends | ||

| 6.59 | 10.61 | Portage Glacier Observation Area Parking Lot | Eastern terminus | ||

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | |||||

==See also==* Glacier Discovery — the Alaska Railroad route that uses the Anton Anderson Tunnel

References

- ^ a b Clark, Maureen (June 8, 2000). "Road to Whittier opens amid protests". Juneau Empire. OCLC 6427731. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Valencia, Kris, ed. (2012). The Milepost: All-the-North Travel Guide (64th ed.). Augusta, Georgia: Morris Communications Company. pp. 549–553. ISBN 978-1-89215429-3. OCLC 427387499.

- ^ Witt, Jennifer W. (2010). Annual Traffic Volume Report (PDF) (Report) (2008-2009-2010 ed.). Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. pp. III–34 – III–35. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ Office of Federal Lands Highway (July 2012). "Forest Highways Fact Sheet" (PDF). Federal Highway Administration. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ Western Federal Lands Highway Division (June 29, 2012). "Program History". Forest Highways. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c Conner, Carla (June 29, 2012). "Alaska Forest Highway Route Descriptions" (PDF). Federal Highway Administration. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 17, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Whittier Access Project. "Virtual Drive". Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel. Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alaska Activity Guide (2012). Alaska Activity Journal. Anchorage, Alaska: Alaska Channel. pp. 74–75. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c Western Federal Lands Highway Division. "FH-35, Portage Glacier and Portage Loop" (PDF). Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ Alaska Activity Map (PDF) (Map). Cartography by Alaska Channel. Alaska Activity Guide. 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c Bridges Department. 2009 Bridge Inventory (PDF) (Report). Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. pp. 39, 125. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ Chugach National Forest, Kenai Peninsula, Northern Half (PDF) (Map) (2011 ed.). Cartography by United States Department of Agriculture. United States Forest Service. January 12, 2011. Map 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Clevenger, Mark (September 1, 2000). "Gen-Sets Provide Standby Support For Nation's Longest Vehicle Tunnel". Diesel Progress North American Edition. ISSN 1091-370X. OCLC 181819196. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Hsu, Roberta; Robinson, Leslie (May 15, 2003). "The Whittier Access Project: Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- ^ a b Whitter Access Project. "Tunnel Design". Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel. Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- ^ "Whittier Tunnel, Transportation & Public Facilities, State of Alaska".

- ^ "Whittier Tunnel, Transportation & Public Facilities, State of Alaska: Schedules and Hours of Operation". Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ "Whittier Tunnel, Transportation & Public Facilities, State of Alaska".

- ^ Alaska Administrative Code, Title 17. Transportation and Public Facilities, Chapter 17.38. Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel. Section 17.38.035. Prohibitions.

- ^ [Railway Gazette International September 2015 pg55

- ^ a b Google (April 25, 2012). "Overview Map of Portage Glacier Highway" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ Kenai Peninsula Traffic Map (PDF) (Map). Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ a b Staff. "Whittier Access Tunnel Traffic Data". Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. Archived from the original on March 30, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ Staff (October 27, 2008). "National Highway system (NHS) Route List" (PDF). Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. p. 4. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- ^ National Highway System Whittier (PDF) (Map). 1 inch=2 miles. Cartography by Division of Program Development. Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. April 2006. Map 09. Retrieved November 2, 2012.

- ^ Slater, Rodney E. (Spring 1996). "The National Highway System: A Commitment to America's Future". Public Roads. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. 59 (4). ISSN 0033-3735. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ a b United States Forest Service. "Trail of Blue Ice". Celebrating Wildflowers. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ Medred, Craig (September 30, 2007). "Benefits abound for late-season camping". Juneau Empire. OCLC 6427731. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ Gorman, Tony (June 21, 2011). Walk to Whittier Returns with New Meaning (Radio Broadcast). Valdez: KCHU. Event occurs at 5:03 PM. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Whittier Access Project. "Vehicle Classifications and Tolls". Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel. Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration (January 1, 2011). "Non-Interstate System Toll Bridges and Tunnels in the United States" (PDF). U.S. Department of Transportation. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ^ Whittier Access Project. "Schedules and Hours of Operation". Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel. Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c United States Forest Service. "Portage Passage Trail". Chugach National Forest. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ Devine, Bob (2006). National Geographic Traveler Alaska. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. pp. 105–106. ISBN 0-7922-5371-X. OCLC 229293402.

- ^ Burks, David Clark (1994). Place of the Wild: A Wildlands Anthology. Washington, D.C.: Shearwater Books. pp. 68–69. ISBN 1-5596-3341-7. OCLC 30814855.

- ^ United States Forest Service. "Begich, Boggs Visitor Center" (PDF). Welcome to Portage Valley. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ Smith, Philip Sidney (1941). Mineral Industry of Alaska in 1939. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 218. OCLC 6743016.

It was possible as late as 1914 to cross from Passage Canal through Portage Pass to Portage Valley by way of a trail over Portage Glacier, but by the 1939 recession and ablation of the glacier had made this route impracticable for summer travel. Because of the numerous large crevasses and serac ice on the surface of the glacier and the unscalable cliffs, the 1939 party found it necessary to climb to 3000 feet to the summit of Portage Shoulder to cross from Portage Canal to Placer Creek Valley

- ^ a b c d e Taylor, Alan; Taylor, Christina (2000). The Strangest Town in Alaska: The History of Whittier, Alaska and the Portage Valley. Seattle, Washington: Kokogiak Media. ISBN 0-9677-8600-2. OCLC 44744551. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Whittier Access Project. "Project History". Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel. Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ Selbig, Aaron (June 19, 2008). ""Walk to Whittier" offers a rare look inside the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel". Turnagain Times. OCLC 39441642. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Burke, Jack (March 1, 2000). "Building the Road to Whittier in Alaska". World Tunnelling. London: Mining Journal. OCLC 232115431. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ Seward Quadrangle (Map) (1953 ed.). Cartography by United States Department of the Interior. United States Geological Survey. 1953. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- ^ Seward Quadrangle (Map) (1955 ed.). Cartography by United States Department of the Interior. United States Geological Survey. 1955. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- ^ Staff (2012). "The National Bridge Inventory Database". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ Alaska with portions of Northwest Canada (Map) (1967 ed.). Cartography by H.M.G. Company. H.M.G. Company. 1967. § D.

- ^ a b Moses, Tom; Witt, Paul (September 14, 1999). "The Whittier Access Project – State of the Art Engineering for Alaska" (PDF). American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 17, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ Hinman, Mike (July 7, 1998). "Group Buys Whittier, Alaska, Building, Plans Condo Complex". Duluth News Tribune. p. 4. ISSN 0896-9418.

- ^ "Whittier Highway Studied". Anchorage Daily News. Associated Press. September 27, 1984. p. C1. ISSN 0194-6870. OCLC 2685131.

- ^ Rinehart, Steve (March 26, 1996). "Whittier Road Due to Begin Cars, Train Would Share Tunnel". Anchorage Daily News. p. 1A. ISSN 0194-6870. OCLC 2685131.

- ^ Kizzia, Tom (December 26, 1996). "Work on Whittier Route set to Begin in March". Anchorage Daily News. p. A1. ISSN 0194-6870. OCLC 2685131.

- ^ D'oro, Rachel (May 7, 1997). "New way to Whittier". Anchorage Daily News. p. A1. ISSN 0194-6870. OCLC 2685131.

- ^ Phillips, Natalie (May 23, 1997). "Court Stops Work on Whittier Road". Anchorage Daily News. p. A1. ISSN 0194-6870. OCLC 2685131.

- ^ a b c Singer, Matthew (September 22, 1998). "The Whittier Road case: the demise of Section 4(f) since Overton Park and its implications for alternatives analysis in environmental law". Environmental Law. Portland, Oregon: Lewis & Clark Northwestern School of Law. 28 (3): 729+. ISSN 0046-2276. OCLC 1568088. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c Staff (2012). "Alaska Center for the Environment v. Armbrister". Environmental Law Online. Lewis & Clark Northwest School of Law. OCLC 233810026. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration (2014). "Section 4(f) Guidance and Legislation". Environmental Review Toolkit. United States Department of Transportation. Section 4(f) at a Glance. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ^ Phillips, Natalie (May 24, 1997). "Whittier Project Back On". Anchorage Daily News. p. A1. ISSN 0194-6870. OCLC 2685131.

- ^ Phillips, Natalie (May 31, 1997). "Whittier Road Work is Off Again". Anchorage Daily News. p. A1. ISSN 0194-6870. OCLC 2685131.

- ^ Hamilton, Vivian (August 1, 1998). "The road to prosperity: state sees funding increase of nearly 50 percent". Alaska Business Monthly. Anchorage. OCLC 49214683. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ Staff writer (July 11, 2001). "Editorial: Civil engineering group recognizes outstanding project". Daily Journal of Commerce. Portland, Oregon. OCLC 61313501. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Campbell, Melissa (November 1, 2001). "Roughing It: Kiewit Construction Takes on the Tough Jobs". Alaska Business Monthly. Anchorage. OCLC 49214683. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ Sorensen, Eric (May 7, 2000). "Alaska town fears flood of visitors when car tunnel opens". The Charleston Gazette. Charleston, West Virginia. OCLC 9334859. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ a b Black, Monica (May 1, 1999). "Alaska Tunnel Gets Millennial Makeover". Railway Track and Structures. Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corporation. 95 (5): 28–30. ISSN 0033-9016. OCLC 1763403. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Clark, Maureen (May 24, 2000). "Alaska Town Braces for Tourists". The Kingman Daily Miner. Kingman, Arizona. Associated Press. p. 3B. ISSN 1535-9913. OCLC 35369410. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ Overview map of Portage Glacier Highway (Map). Cartography by Navteq. MapQuest. 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ Google (October 8, 2012). "Overview Map of FFH-35" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved October 8, 2012.